| Conservation and Management of Cultural and Natural Resources |

| From:Heritap Author:Nobuko INABA PublishDate:2024-03-18 Hits:392 |

| Abstract The cultural heritage management system in Japan not only covers cultural heritage but also natural heritage, landscapes and intangible heritage as well. There are two parallel approaches for the conservation of landscapes: Cultural Landscape concept promoted by the Agency for Cultural Affairs and Satoyama concept promoted by the Ministry of Environment. Despite the different focus and advocators, both approaches aim at connecting local governments with local communities and heritage. Besides the approaches by government, heritage resource management researchers and neighbourhood associations also play an important role in the conservation and management of cultural and natural resources.

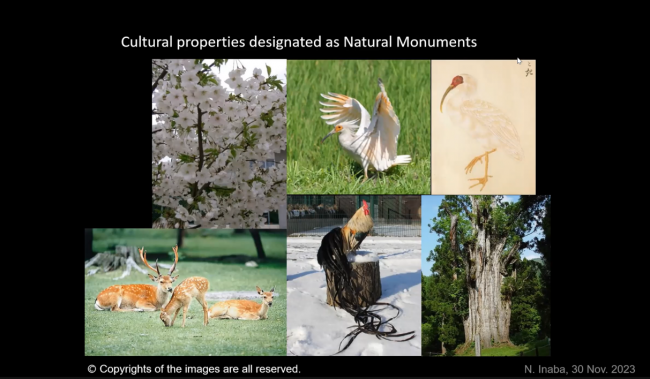

Fig. 1 Cultural heritage in Japan 1. Nature-culture linkages

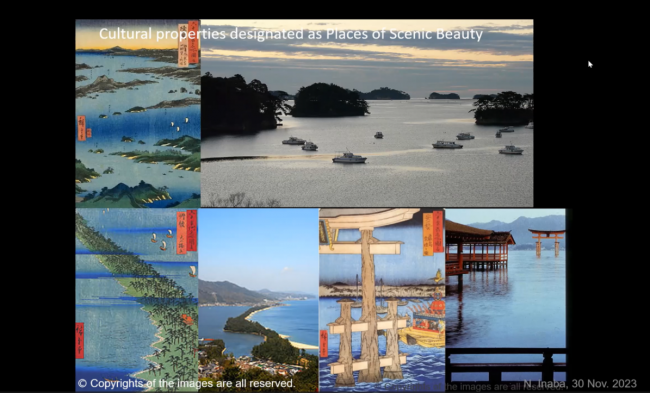

Fig. 2 Natural monuments Certain areas of natural significance can be designated as “Places of Scenic Beauty” (名勝, meishō). The criteria for the designation of places of scenic beauty includes its public popularity. For example, it was once depicted in the paintings, poems or others forms of artistic works. The following picture shows some places of scenic beauty whose sceneries were depicted in ukiyo-e (浮世絵) woodblock paintings.

Fig. 3 Places of scenic beauty In short, keeping natural monument concepts in the realm of a cultural heritage without being absorbed exclusively in nature conservation is an advantage of Japanese legal framework. It reminds people of the original concepts of nature and its relationship with people and culture.

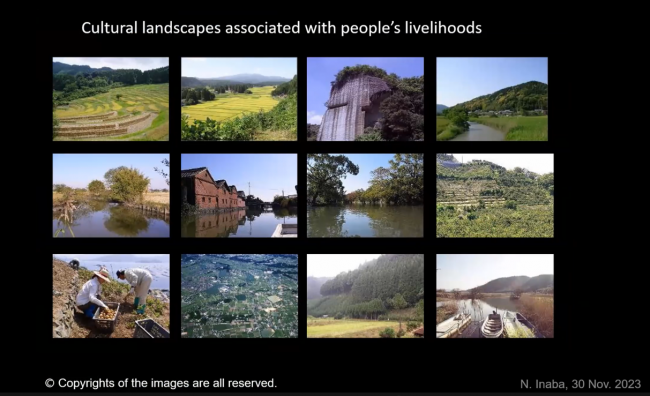

Fig. 4 Cultural landscapes Satoyama (里山) is a Japan term refers to people’s settlements and their fields for livelihood with their surrounding mountain valley slopes. The International Partnership for the Satoyama Initiative (IPSI), organized by United Nation University and financially supported by the Ministry of Environment (MoE) is a good example of contributing the sustainability development domestically and and internationally.

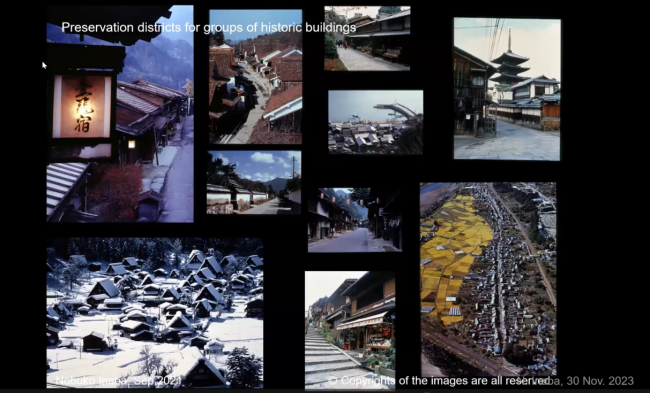

Fig. 5 Cultural landscape concept and Satoyama Initiative 2. Resilience / Risk preparedness Based on the research movements developed by researchers from diverse disciplines, including Minzoku-gaku (民俗学) studies or Japanese native folkloristics, the preservation district system was introduced in Japan. It derived from the nation-wide movements of residents to protect their historical environment, cities, towns and villages. Municipal ordinances were established in many places and finally a new category was introduced in the law.

Fig. 6 Preservation districts for groups of historic buildings The decision-making authority for the preservation district system is given to the municipalities which are closest to the residents and communities. The national government remains in the role of the recognition of national importance, and it provides technical and financial support. One exemplary survey project by Japanese researchers in architecture and agriculture fields is the Millennium-village Project, which studies on villages that appear in a 10th-century dictionary in Japan. These villages are believed to survive with valuable knowledge on the relationship between nature and civilization that people can learn from.

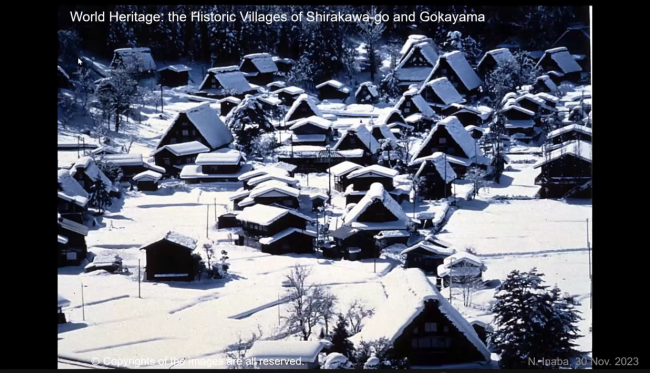

Fig. 7 World Heritage: the Historic Villages of Shirakawa-go and Gokayama · Role of neighborhood associations

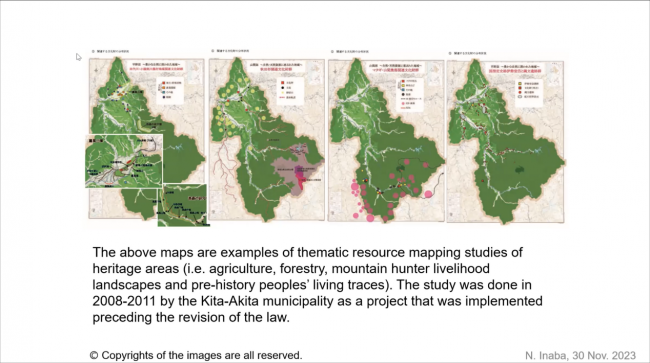

Fig. 8 Japanese neighborhood associations 3. Institutional framework: promoting conservation at local level One of the examples of combing nature and cultural resources together is survey mapping on different themes. The following picture is a thematic resource mapping studies of heritage areas. It reflects where the forested areas are and where prehistoric people lived.

Fig. 9 Examples of thematic resource mapping As mentioned before, Cultural Landscape policy and Satoyama Initiative are two parallel approaches led by the Agency for Cultural Affairs and the Ministry of Environment. Despite the different advocators, both approaches aim at promoting cultural and natural resource conservation and management at the local level. The Agency for Cultural Affairs has been requesting the local governments to develop the plan on a more interpreted approach of nature, culture, and resource management. While the Ministry of Environment works on requiring the municipalities to develop the plan on how to live in harmony with nature, building vibrant communities.

Fig. 10 Satoyama Initiative pamphlet The feature of including both tangible and intangible and both culture and nature in one system acts as an advantage in particular at the local level to help the communities to grasp their resources in a more comprehensive manner, linking all sorts of heritage expressions with their own natural environment. |

|

|

- INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE PRELIMINARY ANNOUNCEMENT & CALL FOR PAPERS

- Observation of the 46th Session of the World Heritage Committee

- Publication | WHITRAP Newsletter No. 63

- Training Workshop on Promotion of Ecotourism in UNESCO Designated Sites held in Mongolia

- The 2024 AWHEIC winners announced at the 46th Session of WHC

- News | UNESCO’s “World Heritage and Sustainable Tourism Programme” Phase II China Pilot Studies - Yellow (Bohai) Sea Migratory Bird Habitat Phase I Training Course Successfully Held

Copyright © 2009-2012 World Heritage Institute of Training and Research-Asia and Pacific (shanghai)